Legatum’s mission: enabling prosperity

Alan is one of four founding partners of Legatum – a global investment partnership that invests proprietary capital in private and listed businesses and focuses on ideas that “enable people to prosper in the fullest sense”.

“Our mission is to generate and allocate the capital and ideas to help others prosper. That’s our motivation. How do we prosper? How do we get better and how do we lift up the most vulnerable in our society? How do we make a more just and equitable world?”

Trying to strengthen societies and change them for the better permanently is an important part of Legatum’s mission — Legatum is the Latin word for legacy, after all.

“We wanted to be mindful of that legacy because we are stewards of it. We are part of a chain that extends back thousands of years of human beings trying to figure out what works and what doesn’t work.”

Linked to this idea, Alan is guided by his philosophy that: “prosperity is the compounding effect of wise choices over time”.

Collaboration and measurable results

Legatum has always given generously, and their philanthropic portfolio included, among many other things, funding neglected tropical disease (NTDs) programmes in Rwanda and Burundi. NTDs are a group of parasitic and bacterial infectious diseases, such as intestinal worms, river blindness and trachoma, that affect more than 1.7 billion people, including more than 1 billion children.

Over four years, the interventions they funded treated more than eight million people for diseases such as intestinal worms, schistosomiasis, and lymphatic filariasis at a small cost. Their work demonstrated the feasibility of quickly scaling up NTD programmes to a national level.

The work provided valuable learning for the Legatum partners who soon realised that applying the rigour used in their investment reporting and due diligence, to smaller, unconnected non-profit community projects was counterproductive.

“We were funding 1600 small-scale community projects across 100 or so countries… but a lot of these smaller organisations had limited capacity on their own – and you’re spending a significant amount of money on due diligence and monitoring and evaluation.”

Realising they still believed in the value of supporting local, frontline organizations, but that their current approach was uneconomic, Legatum, together with their advisory business at the time, Geneva Global, ran ‘strategic initiatives’ – clusters of projects that ran over three to five years in different countries.

With greater collaboration amongst the organizations and greater efficiency, Alan and his colleagues could see they were turning the development dial and achieving “considerable measurable results”.

Setting up The END Fund

“We had about 21 strategic initiatives at one point and we found some of these had real potential to scale. We asked ourselves how do we bring more capital into this space? We’re finding solutions to problems that are really quite profound. We’ve got limited capital – it would be great to learn from others, collaborate and go on a journey with them.”

It was this that led to the establishment of The END Fund in 2012 as a philanthropic platform to bring in others and end neglected tropical diseases.

Since then it has worked with partners to provide more than a billion treatments and has now committed itself to spend the 2020s doing all it can to support efforts to accelerate the elimination of NTDs.

“The END Fund put a goal on the table of ending a set of diseases and ending them in our lifetime. We have not put a date on it but we like to think it would be something like 2044 something in that range – 20 years from now say. These initiatives can accelerate really quickly once momentum builds.”

Working in partnership

One reason Alan and his colleagues are prepared to take risks, evaluate progress, innovate, seize opportunity, strategise and then scale is because they work in partnership. Over time, they have been able to replicate that bond with a wider circle of partners and like-minded individuals.

He notes that a shared goal is powerful in getting the right people in the room together — even if those people may have varying political beliefs.

“Put kids and worms and the desire to do good on the table and it draws people together. It’s a great vehicle for relationship and for peace making and for having a lot of fun, for learning with others.”

He makes clear that the benefits of working with others are myriad: collaboration brings moral support, greater effectiveness, and increased reach, capacity and knowledge.

“I only know so much,” he said.

And the best way to find those people who’ll make all the difference is to be clear from the beginning about what it is you want to accomplish and how you want to go about it. Once those things are in place, you can start looking for the right people to join you.

“People are often drawn to very similar goals and values and so the more you elevate those things the higher your chances are of identifying people who might share the same aspirations as you. It takes a lot of hard work and a lot of serendipity.”

Taking a risk

Even with resources and clear goals and values though, things won’t always go to plan. But the mistakes are all important moments of learning, says Alan.

“Failure usually comes down to around one or two things. One is around people – having picked the wrong leader – they’re poor at execution or are stealing or abusing their power in some way, and the second relates to broken systems, problems that are so deeply entrenched, they are hard to break through.”.

He doesn’t like the word failure though.

“Everything is a feedback loop – it’s telling you something, it’s teaching you something. You want to be learning something the whole time.

“We try to test ideas and scale them. A lot of philanthropic capital is risk averse. We have quite a high appetite for risk. We don’t mind taking a bet and risking failure as long as we understand why we’re failing and are intelligent about it.”

The human importance of giving

Making mistakes, learning from others and seeking connection are intrinsically human traits and it is humans, their motivations and their potential for improvement and growth that are central to Alan’s philanthropic philosophy.

Here are some of the valuable lessons he’s learned over his many years as an investor and philanthropist.

1. Giving is spiritual

“The etymology of philanthropy is love of mankind and people. But it’s irrational.”

“It makes no sense to give something away and expect nothing in return yet we do it. We do so because there’s a psycho-spiritual reward when you’re generous – we feel good and we discover it is truly better giving than receiving.

“We believe that central to everyone’s purpose, joy and fulfilment is the importance of giving to and serving others. We give out of the joy of helping others to have an opportunity to prosper and flourish.”

2. Don’t assume your professional experience will transfer directly to your philanthropy – be aware it’s a journey

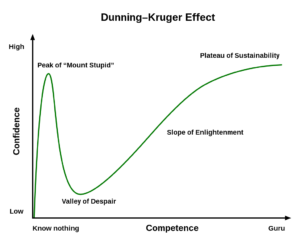

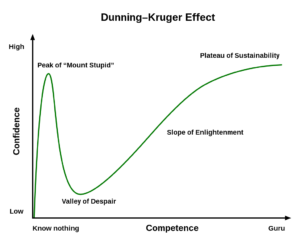

“All philanthropists seem to go on a journey which I’ve observed is best summarised in what’s called the Dunning Kruger effect.”

The Dunning Kruger effect is a cognitive bias where people with low expertise in a particular area tend to overestimate their ability or knowledge.

Alan explains philanthropists have often had a big success in one field and they bring that confidence to philanthropy but then find all the rules are different.

“You suddenly encounter in philanthropy a whole different set of incentives – people in this space are not working for money, and many times not glory, there is ego, but not always.

“In this space, people often forgo income and these other metrics of success for altruism, the chance to help others, the psycho-spiritual reward and the nobility of helping others.

“As you engage in this space, you begin to realise that systemic change is incredibly difficult and you come down the other side and you hit the valley of despair.

“And then you come out the other side and you start to actually realise that there are many solutions out there – but the journey was much much harder than you anticipated.”

3. Get yourself out of the way — focus on raising up the inherent value of others

“What I’ve found helpful is to check my motivations when we engage in philanthropy. There is often the desire to ‘save’ rather than ‘serve’ which can be immensely distortive to programmes. There are often many things we’re figuring out inside of ourselves when we’re engaged in the activity of helping other people and I think having an honest internal conversation is really constructive.

“Having a framework that puts the nobility of individuals at the core and their inherent ability to create and get ahead is really important because you don’t come into a community with a view of saving but with a view of assisting – of coming alongside, and elevating, and creating an enabling environment for people to prosper because that is ultimately what they want to do.

“If you build off the idea that everyone is of value and incredibly capable, then communities are best placed to solve their own problems. They don’t really need outsiders to come in and solve them for them.

“So our observation has always been that what is lacking is often some capital, some structure, some networks and some knowledge.

“Get the resources to those small community-based frontline organisations. We are not there to save, we are there to serve.”

“We discover it is truly better giving than receiving.”

As a donor, what does it take to set yourself a goal so ambitious that it aims to end a class of diseases in your lifetime?

As a donor, what does it take to set yourself a goal so ambitious that it aims to end a class of diseases in your lifetime?