This article was written by Scott Greenhalgh for Beacon Collaborative. Find out more about the author below.

Responsible investing1 (which I define to include ethical, sustainable, impact and social investment) and the pursuit of profit with purpose has grown exponentially in recent years. It has many supporters who believe business and investment can be a force for good and help contribute solutions to our pressing environmental and social challenges.

It also has detractors who worry that shareholder primacy and the consequent prioritisation of profit over purpose, at best limits the ability of business and investment to be a force for good and at worst provides false comfort as to the contribution business can make.

Ahead of the October 2021 Beacon Forum, this article examines some of the key issues in this debate and the role that philanthropists and private wealth can play.

1. The Growth of Responsible Investing

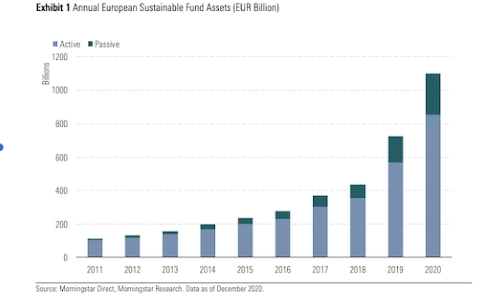

Growth in this sector has been substantial, particularly in 2019 and 2020.

There has been a circa tenfold increase in the size of the responsible investing market over the past 10 years in both Europe and the US. In Europe, there are now some 3000 publicly traded mutual funds with over €1 trillion AUM and in the US almost 400 mutual funds with c $250billion AUM that pursue a core responsible agenda2. The table below highlights the strong growth in Europe.

In private markets, Phenix 2020 data lists3 some 1600 funds worldwide with $330 billion AUM as pursuing a responsible investment strategy.

This explosive growth with the range of active and passive funds covering (almost) all investment strategies offers investors and their wealth advisers a huge choice on how and where to invest in both the public and private markets.

In the UK, in addition to a wide range of responsible mutual funds, there is strong activity in the ethical bond, early stage “tech for good” and social property arena.

2. Does values-based investing generate financial alpha?

The short answer is “yes, but…”

There are many studies that have analysed the return performance of responsible investment funds. Most show outperformance or at least performance equivalent to that of their “traditional” benchmarks4.

A 2019 Morgan Stanley report analysed performance of some 11000 mutual funds over the period 2004 to 2018 and concluded that investors could expect returns equivalent to those of traditional fund counterparts and that responsible investment strategies offered better downside protection to investors in periods of market volatility.

Intuitively this equal or outperformance feels right. The environmental and societal challenges we face are throwing up huge opportunities for those businesses that can adapt and/or innovate to provide solutions to these problems.

Similarly, companies that engage positively with their wider stakeholders and actively consider the ESG factors that affect their business have a better chance of building shareholder value than those that do not. A recent McKinsey5 survey of business leaders shows a clear majority agreeing that pursuing ESG programmes creates shareholder value over the medium to long term.

However, the “but” in the “yes, but” above comes in two parts:

First, there are studies that disagree with the conclusion that responsible investing has led historically to outperformance. These studies6 do not dispute that Responsible Funds have outperformed in recent years, but they argue that this outperformance is not the result of the pursuit of a responsible investment strategy, rather the outperformance is the consequence of other more traditional investment criteria being used in the stock selection process by these funds. By the same token, these studies do not believe that responsible investment strategies offer better downside protection.

The second part of the “but” is that most mainstream fund managers market responsible funds based on the potential alpha or outperformance that they offer. This approach ignores other investor motivations for responsible investing, such as the desire of investors to align their investment strategies with their values and the wish to influence investment funds and businesses to pursue more sustainable agendas. This marketing approach also raises the concern as to what will happen to investor appetite if outperformance were to cease.

3. Do responsible investment strategies have a positive impact?

Here, I will argue the picture is mixed with quite a few positives and some large (current) concerns.

Let us start with the concerns. There has been much in the press about “greenwashing” or “impact washing” with the accusation that fund managers have over-claimed their environmental or social credentials.

In part, this reflects the rapid growth in the responsible investing market and the desire for fund managers to have an investment offering that can participate in this trend; put another way, some managers may not have fully developed their impact strategy, metrics and measurement ahead of the fund launch. It also reflects the challenge of measuring impact, the lack of agreed standards and the different interpretations that can therefore be used to define and articulate impact.

A second fundamental concern relates to the question- does the purchase or or divestment by a responsible investor of an existing share (of fund position) have any impact? The sale or purchase of that share will presumably have no effect on the issuing company’s activities and so on the positive or negative impact of that company.

Arguably it is only if there are enough sellers of a (negative) company’s shares, that access to the capital markets for that company is endangered and so the company’s behaviour is forced to change. This question of the impact or additionality of secondary market transactions can be debated at length.

But there are some positives. These include the efforts by regulators to bring greater transparency, for example through the EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulations that are now coming into force7.

In public markets, data analysis organisations such as Morningstar and Sustainalytics are producing impact metrics and measurement both at a fund and individual (major) company level, enabling comparative performance and changes over time to be measured.

In private markets, there are a number of impact measurement tools in use that allow fund managers to show the impact and changes thereto both of individual investments and aggregated at the fund level. With a few notable exceptions, most private market impact measurement is done by the fund manager and so runs the risk of not being impartial.

It is important therefore, in my view, for investors to help drive positive change by asking fund managers (and through them the companies in which they invest) to explain in detail how they define and measure the impact they have, how they factor ESG criteria into their decision making and then to hold those managers to account for the impact they report.

4. Shareholder v Stakeholder Capitalism and will the latter lead to sufficient change?

It is 50 years since Milton Friedman’s essay that argued that the social responsibility of business was to maximise the financial return for shareholders and that decisions should be taken by the directors of companies on the basis of what would be best for (long-term) shareholder value.

In more recent years, in line with the growth of the responsible investing movement, there have been increasing calls for business to adopt an approach of stakeholder capitalism whereby decisions are taken with a view to their impact on all key stakeholders (for example, customers, employees, the environment, the community) as well as on shareholders. The US Business Roundtable declaration in mid 2019 by the CEOs of major US companies and the manifesto of the 2019 World Economic Forum calling for business to embrace a stakeholder rather than shareholder capitalism model offer important milestones and evidence of this trend among global business leaders.

Stakeholder capitalism seems therefore to be winning. But will it really make a difference as to how investors and businesses operate? And will that difference be enough to address the challenges we face? These are massive questions that merit careful debate beyond the confines of a short article.

My own view is that much of the current thinking around stakeholder capitalism follows a ‘business as usual” approach that does not go nearly far enough in rethinking our economy, the role of investors and investment and the constraints on their ability to be a force for good. Let me set out my reasoning below:

Company Law

For the most part company law continues to give primacy to the interests of shareholders. For example, in the UK, the 2006 Companies Act requires directors to consider a range of factors (employees, community, environment) in their decision making in order “to promote the success of the company for the benefit of all its members/shareholders”.

In the US, Delaware law (where many companies are incorporated) also gives clear primacy to shareholder interests. It can be argued therefore that the law limits directors in their consideration of stakeholder interests to those that do not adversely affect shareholder returns.

Lockstep

It is often argued by responsible investors that commercial success and positive environmental or social impact go hand in hand.

This means there is no trade-off between doing the “right” thing and doing well. Work by McKinsey suggests that this holds true especially over the long term of 5 to 7 years8. Clearly to the extent lockstep exists, the limitations of shareholder primacy can be mitigated.

However, one only has to look at the substantial negative externalities across a range of industries (for example tobacco, social media, mining) to make a powerful case that lockstep is more the exception than the rule, especially over the shorter term and that there are trade-off’s between maximizing social and/or environmental impact and financial returns.

Incentives

For the most part, incentives for directors of companies remain financial and share-value based.

Career progression-related incentives are similarly largely driven by measures of financial success. At the major fund management firms, individual fund manager and fund performance is typically based on benchmarking that fund’s performance against its peer group (we are back to alpha) and growing the AUM of the fund and so the fees the fund generates for the firm.

Even in the world of impact investing, performance incentives based on impact rather than financial success remain relatively rare. Remuneration in the fund management industry therefore reinforces shareholder rather than stakeholder primacy.

Alternative corporate forms

There are alternative corporate forms that allow for greater balance between stakeholder and shareholder interests. All of these different corporate forms are growing in number, but they remain a small part of the overall private sector.

For example, in the US, Public Benefit Corporations are for-profit entities that call for decisions to be based on balancing shareholder and stakeholder considerations and for profits to be based on delivering positive societal or environmental impact. However, these PBCs remain few in number with c 10 publicly listed and some 4000 overall9. PBCs are authorized by laws in many US states and so offer an established and “enlightened” corporate form; rapid expansion of PBCs (and their equivalents in other countries) might allow business to play a far greater role in addressing our environmental and social challenges.

The BCorp movement is a well-regarded accreditation process that allows companies to seek certification as a responsible business. However, BCorps do not have the force of company law behind them. In the UK, the Employee Ownership Association lists 730 employee-owned businesses, John Lewis being the largest and most well-known example10. Such businesses will, of course, focus on employee interests as opposed to those of other stakeholders.

In the impact investing world, most funds seek market-based returns. This leads to them operating within the same constraints as traditional investors. There are however a few funds that place impact first, offering investors a lower but “sufficient” financial return in the belief that this allows the fund to help generate greater impact.

I ran one such fund; the key challenge lies in making transparent the judgments and trade-offs between financial and impact returns. I was also fortunate as the fund performed well (above its’ financial target of 9% p/a net return to investors), so we never had to face the challenge of maintaining impact returns in the face of weaker financial ones.

My argument is therefore that current legal and incentive structures serve to reinforce a shareholder primacy that limits wider stakeholder considerations to those that do not jeopardise the ability to maximise financial returns. The good news is that alternative models exist; we need to see their widespread adoption.

So, what can philanthropists and private wealth do?

The above article has given a brief overview of some of the key challenges and debates within the responsible business and investment communities. Views will vary on all of the above points and the role that business and investment can and should play in addressing our environmental and societal challenges.

Among the actions that philanthropists and investors might take are the following:

- To engage with the debate about corporate purpose, corporate legal form and the opportunities, limitations and challenges of our current economic system.

- To scrutinise wealth managers, funds and companies in which one invests to understand how they address the stakeholder/shareholder primacy question.

- To engage with the measurement of impact and to push for as much transparency on this as possible.

- To consider the trade-offs inherent in investment portfolios and the extent to which one can allocate (part of) a portfolio to higher impact investments.

- To consider* whether a change of statute/corporate form or BCorp certification would be helpful in building long-term value and delivering greater environmental and/or social impact.

*in a business the philanthropist controls.

References

- Throughout this article I use ‘responsible investing’ as the overarching term for ethical, sustainable, impact and social investment. It therefore incorporates investing that uses Environmental, Social and Governance factors to inform decision-making.

- Morningstar Direct 2020 data.

- Phenix Capital Jan 2021 Impact Fund Universe Report.

- For example see Morgan Stanley “Sustainable Reality” 2019 or an older systematic review “ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies” by Friede, Busch and Bassen Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment 2015.

- McKinsey 2020 “The ESG premium: New Perspectives on Value and Performance.”

- For example, see Scientific Beta 2021 “Honey I Shrunk the ESG Alpha”.

- EU SFDR phase 1 became applicable in March 2021.

- McKinsey November 2019 “Five Ways ESG creates value.”

- Forbes June 2021.

- See John Lewis’ Employee Ownership Association