“I hope my apology and reparations for my family’s slave-owning past will set an example to others.”

Laura Trevelyan was working as a long-serving BBC journalist and news anchor when in 2016 she found out from a distant relative that some of their ancestors had been slave owners in the Caribbean. The discovery would take Laura on a journey to Grenada and propel her from journalist to philanthropist and full-time advocate.

Laura Trevelyan is quite honest about her reaction when she was first told by a distant cousin that some of her ancestors had been absentee slave owners in Grenada in the Caribbean.

“I wasn’t horrified. I just thought it was interesting,” she said. “I thought about it from the journalists’ perspective — what an interesting story. Interesting that some of them were absentee slave owners as well as all the other prominent things they did.”

The Trevelyans are an ancient family with a significant history in 19th century and early 20th century Britain.

Laura’s great-grandfather was the best-selling historian George Macaulay Trevelyan. He was descended from writers, politicians and reformers in the 19th century including Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan – a civil servant and reformer widely regarded as being the father of today’s modern civil service. However he’s also remembered for being responsible for Britain’s failure to send aid to the Irish during the potato famine during which a million people starved to death.

In 2006 she wrote a book about her vast family history – A Very British Family: The Trevelyans and Their World – but even with all the research she did, she had never come across any information about her family being slave owners. Not even by her historian great-grandfather.

“George Macaulay Trevelyan writes about the abolition of slavery and what an achievement that is but completely glosses over a) Britain’s involvement in the slave trade and b) his own family. He doesn’t mention any of it.”

It would be another ten years before she learned of the connection.

In 2014 University College London published an online database called The Legacies of British Slavery into which they put all the records of compensation for everyone that received money when slavery was abolished in 1833.

Laura, who has lived in the United States since 2004, said she remembered reading stories about the database crashing because so many people tried to go on it but never went on it herself.

But someone in her family did.

In 2016 her cousin John Dower wrote to her to say “Laura — you’re the journalist, did you know about anything about this?”

“I thought ‘Oh gosh this is embarrassing’ – I didn’t realise and no one in the family had passed down this crucial piece of information.”

‘The death of George Floyd forced me to act.’

In 2016, when she learned of the connection, Laura was busy with family life and working life anchoring a news programme for the BBC, covering the US elections when Trump became president.

“My cousin John was shocked and appalled when he first found out but I lodged it away,” she said. “At some point I knew I wanted to explore it further.”

But things changed in 2020 with the death of George Floyd and the progression of the Black Lives matter movement.

“With the death of George Floyd I was really forced to think about it. We were covering it every night in our programme. Covering protests in New York. I began to join the dots a bit and I thought if this was the legacy of slavery in America – of police brutality to black people – what does it mean for people in the Caribbean?

“My ancestors were slave owners and what’s the debate in the Caribbean about Black Lives Matter? The ripples went around the world including to the Caribbean.”

A journey to examine the past and explore the present

Laura’s relatives had been absentee slave owners on the island of Grenada in 1833 so she asked her BBC bosses if she could go there to explore that debate and use her own family history as a way into it.

In February 2022 Laura travelled to the island to make the documentary.

Watch a BBC news clip of Laura’s journey to Grenada.

During her visit she met local historians, academics at the University of the West Indies and local groups to learn more about her family’s history and role as slave owners and to see the legacies of slavery that still very much exist.

“Everyone I met in Grenada, I asked ‘What do you think I should do? What responsibility do I have?’ And everyone I met said ‘Yes, you do have a responsibility and yes you should do something.’”

This included paying money and she agreed.

“If you can, you should. My family got everything and their families got nothing so there’s a very clear moral responsibility plus also slavery is not just in the past – there’s tremendous rural poverty in Grenada, there’s lack of opportunity for many people, a legacy of poor health and inherited trauma.

“So the idea it’s in the past – it just isn’t. The argument ‘But it was hundreds of years ago’ doesn’t really wash.”

A far-reaching family debate

When the documentary went out in May 2022 it prompted a wider debate in the family about what they should do in response.

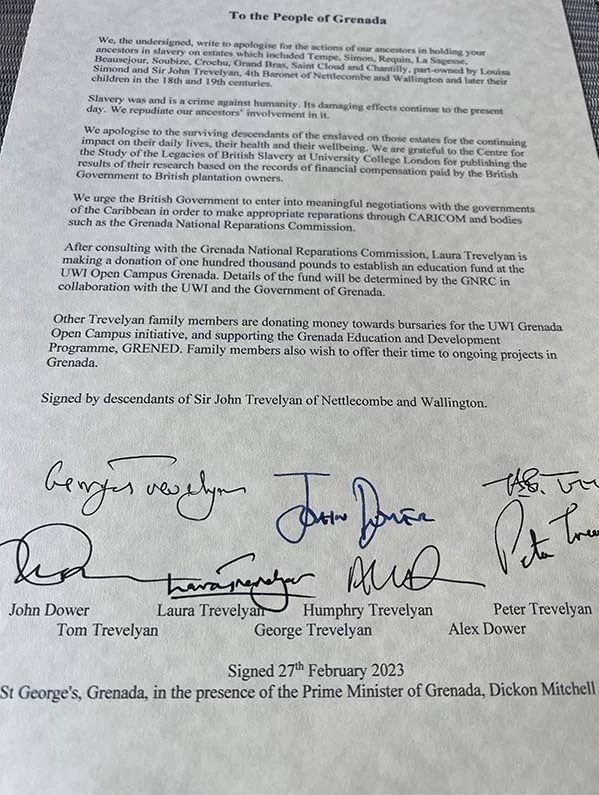

The Trevelyans’ letter of apology to the people of Grenada (Pic: Laura Trevelyan)

And her family is huge. From Sir John Treveylan in 1757 – there are 1,000 family descendants with two branches in the UK – one in the Northumberland area and one in the west of the country.

The west of England branch contacted her and cousin John organised a family Zoom call with at least 50 people on it.

CARICOM, the body that represents the Caribbean Community across 20 countries, has developed a ten-point reparation plan. Step one is an apology.

“There were some family members who philosophically felt you can’t apologise for something that you didn’t do – you can’t apologise on behalf of someone else.”

Others in the family felt it was a hornets nest where nothing good could come of stirring up the past. Some were worried that by apologising the family would be opening itself up to possible legal liabilities. Others were concerned about the family’s reputation and legacy, not wanting it to be polluted by an association with slavery.

“It is all logical and understandable but it was the minority view,” Laura said.

Some family members started sceptical but came on board as they learned more.

Her 80-year-old Uncle Tom, a GP, was one of those who was unsure but after reading widely on the topic and listening to the arguments came round to the idea of apologising.

“Because he is a healer, he became convinced of the healing power of apology and actually became in charge of drafting a family letter of apology,” Laura said.

Sir Hilary Beckles, the Vice Chancellor of the University of the West Indies and the chair of CARICOM’S Reparations Committee addressed the family’s online meetings as well.

He told them how he had read Trevelyan as a child and a student and how it was meaningful that this family of historians now has its own historic role to play.

“He saw that way more clearly than we did,” said Laura.

A public apology and a personal payout

In February 2023, Laura and a group of other family members travelled to Grenada to a ceremony in which they publicly apologised for their ancestors’ involvement in the slave trade in 1833.

Laura also pledged £100,000 – taken from her pending pension payout at the BBC – in reparations with more money due to come in from other family members via a charitable organisation they are currently setting up.

Trevelyan family members at the public apology ceremony in Grenada in February 2023. (Pic: Laura Trevelyan)

After consulting two people on the reparations committee who both suggested spending money on education, the £100k has been used to set up student bursaries at the University of the West Indies.

“I was struck by that in Grenada after we had apologised publicly for what our ancestors had done, people said ‘This really means a lot’. One woman said to me ‘This feels like a burden has lifted that I didn’t know I was carrying.’

But apologising has not been straightforward she says. Laura says she has faced criticisms that it’s all a token effort to assuage guilt, that £100,000 is a tiny amount of money compared to how much her family would have made and that it won’t change or affect anything.

“I think part of the importance of those descended from slave owners is its important to come forward and put a face on slave ownership. Difficult thought that might be and upsetting for people in the Caribbean – you can only do that by personalising it really,” she explains.

Her actions have prompted others to come forward too.

Journalist and author Alex Renton has a similar ancestral history in Jamaica and together he and Laura have launched a group called Heirs of Slavery to encourage people with this past to come forward.

So far more than 70 people who are descendants of slave owners have been in touch.

“Some people want to explore it more. Some people actively want to do something and they want to know how.

“I talk to people about the value of apology and connect them with different reparations committees on the different islands.”

Transferring her skills to a new mission

Laura’s new knowledge into this area of slavery and reparations has captured her head and heart so much she has now left the BBC to become a full-time advocate.

She’s even been made an honorary fellow of the Patterson Institute of African and Caribbean Advocacy.

“When we went to Grenada to apologise there was just this global reaction to what we’d done and how could they do something similar. I realised I had shifted from being a journalist to being an advocate.”

While still at the BBC, she was asked to write articles about what King Charles should do on the topic of reparations and apologising for the Royal Family’s connection to slavery.

“I wanted to say ‘The King should apologise’ because the Royal family sanctioned and participated in the slave trade since its inception but I could not say that because I was writing as a BBC name.

“I realised I couldn’t say what I really wanted to say or do what I wanted to do within the confines of the BBC.”

In Grenada, Laura spoke with with a group of students who told her what life was like living with the legacies of slavery. (Pic: Laura Trevelyan)

Her trip to Grenada had taught her the power of being able to advocate so three weeks after returning from her trip she announced she was leaving the BBC.

“It just felt like a new path had opened up without me really realising it. There was a role that maybe I could play that I uniquely fitted to because of my public speaking skills, storytelling skills, the profile the BBC had given me – all of these things.

“There is so much pain in the Caribbean about slavery. As a journalist I’m used to asking why things happen and where does power lie?

“It’s been incredibly interesting although to be part of the story is surreal. But the idea of setting an example rang very true to me. It seemed important to try and do that.

“But all of this has been orchestrated by Sir Hilary Beckles – he was the one who saw the potential in us. And so I’m really following his lead.”

Interrogating our own histories

Laura has since visited different Caribbean countries to meet the people working towards apologies and reparations from Britain, France, Spain, Portugal and the Netherlands.

Success, says Laura, is a multi-step process.

“First, we want an acknowledgement of the horrible impact of slavery and not to brush it under the rug which has been the British way. We only celebrate abolition and we don’t talk about its legacy.

“Secondly an apology – but also then what should you do. It’s important these two things are linked.

“Thirdly, we need to encourage governments to apologise because it’s only government who can give at a level that Caricom is asking for — to invest in healthcare, education, and to forgive debt.”

To those that believe slavery has nothing to do with them, Laura would point out the whole of the United Kingdom has benefited from slavery.

She said: “People’s freedoms were taken away from them and the profits that were made helped people get to where they are today.

“Do you think your own position in society today relates in any way to the wealth and social standing that your ancestors derived from slavery? Can you really answer that question honestly and say ‘No my position is all down to me, I didn’t have anything I inherited through my ancestors. Is that really the case? Did you do everything on your own? Make every single connection? Is that really true?

“That attitude of ‘Nothing to do with me’ is a lot to do with how we were taught – it’s not surprising that people don’t make the links because why would you? So many aspects of the slave trade in Britain and that was not taught to my generation but I think it’s being taught now so future generations will look at it all differently.

“And now the link has become a bit embroiled in the culture wars and politicised but I would say it is important to step outside the polarisation.

“That’s why the more families that tackle this and think about it the better.

“Be brave. People want to hear from you.”

Useful links:

Search the UCL Legacies of British slavery website.

Watch Laura’s visit to Grenada

Listen to Laura’s documentary in full on the BBC World Service

Further reading: