Read more about funding for the Arts & culture here.

Place-based Philanthropy:

The rationale for culturally-driven regeneration projects

Written by Paul Callaghan and Paul Williams. Originally for New Philanthropy for Arts & Culture, a project supported by Beacon Collaborative. January 2021. More about the authors below.

For many people, potential philanthropists among them, the phrase “L’art pour l’art” or in English “art for art’s sake” defines its role and importance as being artistic and not for other reasons. Donors have contributed to save great works of art ‘for the nation’ simply because they are great works of art. The rationale for funding an orchestra is often focused on the quality of the music it produces rather than the wider benefits that it brings to society.

Yet, in today’s complex world, “art for art’s sake” is only one element of what culture can deliver. In fact, the importance of art and culture is that it can be a means to achieve other ends that touch not just the artistic soul of the individual but have a much wider impact on society as a whole. Culture can be used as a sophisticated tool to strengthen social cohesion, increase personal confidence and improve life skills. It feeds into the economy, health and learning. It can help us to cope with things like loneliness and fill us with hope. It can strengthen our ability to act as empathetic and democratic citizens at the same time as creating innovative training and new employment routes.

Culture has always mattered and today it matters more than ever for our society. It helps give a place to its values and identity. It inspires, empowers and elevates those who live, work, and enjoy where they live and as such it should be placed at the centre of economic and social regeneration.

So, in assessing the value of art and culture we must recognise the role cultural activity has to play as a tool for urban regeneration and place-shaping and also as something that inspires creativity and innovation, changing individuals as well as places.

Theatres, galleries, cinemas, libraries, or concert halls are all integral parts of a thriving society as they create a vibrancy in communities, entertainment for residents, and are a source of happiness and inspiration. Our society needs to have a cultural soul. There need to be opportunities where people can develop their cultural talents, a place where people can go to see or create great art and a place that helps other people realise that their own creativity is important and inspires them.

One of the biggest drivers of a successful place is confidence and culture can provide this. This is not just about cultural infrastructure, it is also about the activity that happens such as concerts, exhibitions, design competitions or children’s craft workshops that promote expression, celebration and achievement and embody the values and identity of a place, cultural activities that express local distinctiveness and that encourage civic pride. What is more, citizens are empowered through the creation of civic pride and social cohesion, and they feel more connected and content. It also generates prosperity by attracting visitors, investors and people who wish to study or live there. It can drive high growth creative businesses and stimulate both a day-time and night-time economy that have benefits that are far wider than those enjoyed by the artists or the venues. Culture tends to spread prosperity much wider through society as it creates jobs and opportunities and adds to people’s confidence and pride in where they live.

From an economic standpoint, we need a society that puts arts and culture at the heart of its towns and cities. There is nothing ‘nice to have’ about the arts and the creative industries. Arts and Culture are central to our economy, our public life and our nation’s health. Cultural and creative industries are typically labour-intensive, employing people in the community and creating jobs that cannot be done anywhere else. They increase footfall and spending not only in the cultural activity itself but also around it. With the decline of high street retail as the main driver of towns and cities it is more important than ever to encourage, develop and fund cultural venues and cultural activities in our towns and cities.

From an economic standpoint, we need a society that puts arts and culture at the heart of its towns and cities. There is nothing ‘nice to have’ about the arts and the creative industries. Arts and Culture are central to our economy, our public life and our nation’s health. Cultural and creative industries are typically labour-intensive, employing people in the community and creating jobs that cannot be done anywhere else. They increase footfall and spending not only in the cultural activity itself but also around it. With the decline of high street retail as the main driver of towns and cities it is more important than ever to encourage, develop and fund cultural venues and cultural activities in our towns and cities.

But how does art impact people and society? It is extremely difficult to quantify and this intangibility often proves problematic when trying to convince funders and donors of the importance of arts funding, since the significance and merit of the arts cannot be judged by popular consensus and numbers alone. Yet, culture should be for the masses, not the few. This should not just be ‘popular culture’ but access to all forms of culture for all. This is not an equity argument – although it easily could be. No, this is a social and economic argument. The right to access or participate in great art and culture should not be a function of where you are born or where you live. It should be there for all, irrespective of socioeconomic standing or postcode.

The most creative people often come from the most unexpected places and by widening participation and investing in the arts and creative industries we can take culture and creativity into the heart of communities and fundamentally change places forever. It will come as no surprise that the areas with the lowest participation rates in arts, culture and creativity are also the poorest communities, places with significant physical and mental health issues, low educational achievement levels and challenges of social cohesion.

Through cultural development we can change places in a number of ways, for example:

- Help a place, and particularly its young people, to grow more confident, raise aspiration and attainment levels and create many more opportunities to develop.

- Build a society that is more inclusive and can help tackle issues of discrimination, loneliness and social isolation.

- Create a healthier populace and increase the wellbeing of citizens.

- Create a better place in which to live and work, embedding sustainable social change as central to the future.

The cultural multiplier, the return from focusing attention, encouragement and investment in culture, is so much greater in poorer places because it is in such towns and cities that culture is not just a ‘nice to have’, it is a fundamental game-changer and becomes a powerful force of regeneration, both culturally and economically. It has a positive relationship with health, crime, society, education, confidence and well-being. It isn’t an ‘either/or’ situation, it is an ‘as well as’ situation.

Culture-led regeneration schemes, defined as a model in which “cultural activity is seen as the catalyst and engine of regeneration”, focus on a number of common goals. The vocabulary employed in each application can be different, but the goals can be roughly grouped into three categories:

- Production;

- Consumption;

- Regeneration.

Production goals relate to the levels of cultural production within an area, seeking to boost the local economy by creating sustainable jobs in cultural production, developing original cultural output that can then be exported across the country and the world. Consumption goals focus on increasing cultural consumption, increasing audiences and creating the designated ‘quarter’ as an attractive destination for cultural visitors to the city. This also feeds into the wider economy of the area, often stimulating the night-time economy in particular, generating a non-cultural economic benefit as a by-product of the increasing cultural consumption. There are also important considerations of diversity in those that are both involved in creating cultural activity and in enjoying it.

In the complex and multi-layered society in which we live we must consider how best to address issues of ethnicity, gender diversity and disability. We have to reach out to people of all social classes and ensure that the cultural activity that we promote and encourage is relevant to the society in which we live. A good example of this is the Newcastle ‘City of Dreams’ initiative led by the Newcastle Gateshead Cultural Venues which targets children in care and children who are carers and aims to give them opportunities to become involved in cultural activity in a way that would not have been envisaged in the past. Consumption is not just about getting the traditional audience to go to more events – that is relatively easy. It is about widening cultural participation throughout all parts of society.

Regeneration goals specifically relate to the built environment, and revolve around the maintenance, creation and renovation of buildings and other cityscape elements. In many cases, cultural quarters are anchored by the development of ‘flagship’ buildings, which both represent a new element in a city’s environment and act as a symbol of the development itself.

The Warwick Commission Report Enriching Britain: Culture, Creativity and Growth highlights the generation of a sense of identity, place and community as one of the key functions of culture and cultural activity, transcending the economic benefits of a flourishing artistic and creative sector.

Barriers to Place-based Philanthropy

- Often Arts and Culture is not seen as a priority for potential donors and it is often only when the donor has a specific or personal interest in a certain art form, organisation or place that leads to involvement and giving.

- Cultural activities are often seen as unquantifiable and very subjective and so it is sometimes difficult to see what a difference a donation would make.

- The perception is that culture is somehow elitist. Giving money to help the educated middle classes enjoy something that they could afford to pay for.

- There is often the lack of a credible ‘landing site’ for donations. Many cultural organisations are seen as too small, run by volunteers and consequently not having sufficient levels of expertise, experience or governance. This may be an organisation like the Community Foundation but better still if it can be a trusted, well-managed and well-governed cultural organisation that has clear goals and measurable outcomes.

- There are not enough ‘exciting’ cultural projects that will attract philanthropists. Cultural organisations are usually looking for revenue support while philanthropists prefer high-profile capital projects.

- There has been too often a lack of matched funding because local authorities are strapped for cash and have no access to European Social and Cultural Funds.

- Many cultural projects are seen as being ‘Public sector’ led either by Local or National Government and there is consequently a view that there is no need for private money.

- There is generally a lack of understanding by the public sector and specifically local government of philanthropic motives (why would people give money away – surely there is something in it for them) and by philanthropists wary of the public sector bureaucracy.

Reasons for Place-based Philanthropy

- The nature of philanthropy is to do good to all. Therefore, projects that have a wider impact are seen as good.

- If planned, researched and monitored they can be quantifiable and measurable with impacts in:

- educational attainment;

- health measures;

- jobs and employment;

- societal change;

- reduction in loneliness and social isolation

- If these can be seen holistically as a ‘common good’ then delivering such outcomes through arts and cultural activity makes funding much easier. So, for example, someone who is interested in tackling loneliness and isolation in older people could recognise the benefits of a choir or a writing group. This gives shape to a common cause approach to alleviating some of our more intractable societal problems.

- There can be a level of personal satisfaction as the donor is seen to be a driver of change

- The wish to give something back to one’s hometown – the diaspora effect.

- Potential family interest and affinity.

Challenges in finding Philanthropists in the Regions

- The poorest places often have the lowest number of successful entrepreneurs as they are often areas of industrial decline and change. Consequently, it is often a shallow pool in which to fish.

- Poor areas have more needs and so more demands on philanthropy.

- Sometimes it is difficult to create a diaspora contact list because the University is often doing this and offering honorary degrees to successful people from the area, often seeking some generous giving afterwards.

How best to encourage Place-based Philanthropic Giving

- Have a safe and clear landing place for donations.

- Establish trust in the organisation and those who run it.

- Establish a track record of doing good work and good deeds.

- Develop a new venture – whether this is a new cultural venue, cultural project or cultural initiative.

- Develop personal connections or use established fundraisers.

- Organise influencer and showcase events.

- Potentially offer naming rights, either personally or corporate naming.

- Raise money through an intermediary organisation such a Community Foundation or the High Sheriff Fund.

- Encourage legacy funding.

- Have a clearly defined project that is:

- feasible;

- shows support from elsewhere including other funders such as Lottery Funders, trusts and foundations;

- Where possible align the objectives of projects to the interest of the donor.

- Introduction to Philanthropists: Ask potential donors to become:

- Board Member;

- Patron;

- Custodian;

- Friend.

Case Studies of culturally-driven regeneration projects

NewcastleGateshead

NewcastleGateshead is a prime example of a culturally-led, place-based regeneration. Initially led by the two local authorities with cultural ambitions, over the last twenty years it has done much to make Tyneside a cultural and creative hub. Its bid to be European Capital of Culture 2008 was a reflection of this and although it was unsuccessful the process of cultural regeneration continued with the attraction of large public cultural events and encouragement of local participation with the arts.

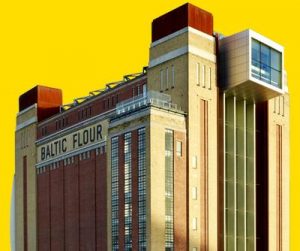

Investment into new infrastructure has included Baltic art gallery, Sage Gateshead music venue and Live Theatre’s LiveWorks development. Partnerships between regional development bodies, both local authorities, Arts Council England and the jointly created Newcastle Gateshead Initiative (NGI) has maintained strong focus on culture and allowed an understanding of the needs and possible impacts of attracting creative sector businesses and practitioners to the region. This has also led to an increase in tourism which now employs over 10% of the region’s population. These cultural policies have undoubtedly helped to improve both the image and the economy of the city-region.

The regeneration of the Quayside area presents a perfect example of a multi-stage project. The two sides of the Tyne have been linked by the construction of the Gateshead Millennium Bridge and this has seen a marked boost to the area’s night-time and non-cultural economy and the Quayside became one of the most important attractions for visitors to NewcastleGateshead, incorporating iconic new buildings and vibrant, exciting nightlife.

NewcastleGateshead Quayside is a good example of the successful pursuit of regeneration through active intervention. Prior to the Quayside redevelopment, the area was severely depressed, lacking attractions for visitors and suffering economically as a result. The Baltic Flour Mills, now repurposed as BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art had closed in 1982, at the loss of 170 jobs in the local economy. Despite remaining a notable local landmark, by the 1990s it had come to represent the failures of the local economy. The redevelopment of the building saw it celebrated as a symbol of a town and an area ‘on the up’, an identification which became a distinct advantage for the Quayside redevelopment as local people took ‘ownership’ as a source of local pride that regenerated a local identity as much as it did the local economy.

NewcastleGateshead Quayside is a good example of the successful pursuit of regeneration through active intervention. Prior to the Quayside redevelopment, the area was severely depressed, lacking attractions for visitors and suffering economically as a result. The Baltic Flour Mills, now repurposed as BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art had closed in 1982, at the loss of 170 jobs in the local economy. Despite remaining a notable local landmark, by the 1990s it had come to represent the failures of the local economy. The redevelopment of the building saw it celebrated as a symbol of a town and an area ‘on the up’, an identification which became a distinct advantage for the Quayside redevelopment as local people took ‘ownership’ as a source of local pride that regenerated a local identity as much as it did the local economy.

Alongside the redevelopment of the existing urban landscape, the Quayside redevelopment also saw the construction of entirely new flagship buildings, most notably Sage Gateshead, opened in 2004. Sage Gateshead occupies a commanding position on the south side of the Tyne, occupying a plot of previously derelict industrial waste ground. This demonstrates the other side of the successful regeneration of the Quayside, the development of iconic new buildings which have been embraced by the local community, and now represent the place and the area to the region and the world. The active intervention and pursuit of regeneration through the redevelopment of the Quayside has revitalised a previously distressed area of both Newcastle and Gateshead and brought substantial economic benefit. The redevelopment of the NewcastleGateshead Quayside demonstrates the way in which ‘flagship’ developments can be blended with existing, iconic sites, in order to create a vibrant and exciting environment for cultural activity.

The major cultural infrastructure developments – Baltic, Sage and LiveWorks – all benefited from significant philanthropic giving. The initial investment by the public sector and the lottery funders has encouraged major matched funding from local philanthropists and national and local trusts and foundations. While this was initially as part of the capital build campaign, it has continued with philanthropic support with respect to programming, outreach, musical education and funding for the Royal Northern Sinfonia. One disadvantage is that the needs of these cultural organisations has reduced the capacity of other cultural institutions in the region to raise funds.

Sunderland

Despite having a population of 270,000 and being the seventeenth largest city in the UK, Sunderland has, for much of the last 40 years, been regarded as Tyneside’s poor neighbour. Between 1988 and 2008, it saw the closure of all four of its main industries: Shipbuilding, Coalmining, Glass-making and Brewing, losing more than 30,000 jobs out of a workforce of approximately 120,000.

The growth of Nissan and out-of-town call centres did much to reduce mass unemployment but did little for a city centre blighted by low footfall, a poor retail offer (competing with out of town shopping malls) and limited cultural attractions. By 2010 about one-third of the city’s retail properties were empty and the National Glass Centre (NGC), Sunderland’s Millennium Project, was close to financial collapse.

The growth of Nissan and out-of-town call centres did much to reduce mass unemployment but did little for a city centre blighted by low footfall, a poor retail offer (competing with out of town shopping malls) and limited cultural attractions. By 2010 about one-third of the city’s retail properties were empty and the National Glass Centre (NGC), Sunderland’s Millennium Project, was close to financial collapse.

At this point key partners began to take action to regenerate the city through culturally-based initiatives. The University took over the NGC to give it financial sustainability and the newly formed, philanthropically-led charity, the Music, Arts and Culture Trust began to work with the University and subsequently the City Council to develop plans to significantly regenerate the city centre using culture as a catalyst. This involved the establishment of a new organisation, Sunderland Culture, a partnership between the University, the Council and the MAC Trust to be the strategic lead and operator of the city’s cultural transformation.

The Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art was reinvigorated through a relocation to the NGC. The Culture Quarter development under the MAC Trust involves the redevelopment of a group of historic buildings and the construction of a new auditorium as part of a masterplan for the area. These buildings, all used for arts, creative and culture purposes, include theatre, music and dance spaces, galleries, facilities for new cultural enterprises and music and artistic education centres and collectively form the vibrant and creative cultural heart of the city.

The funding for this ambitious regeneration of the centre of Sunderland through arts and culture has come from a number of sources. The two Lottery Funders agreed to commit about £10m to a project that was culturally ambitious, restored key heritage buildings and regenerated a part of the city that had been in decline for over 30 years. Support of approximately £4m, both in cash and kind came from Sunderland City Council. The remaining £6m has come from the MAC Trust, other trusts and foundations and significant philanthropic donations.

Creating places where art and culture can be produced, practiced, delivered and enjoyed is at the very heart of the vision for the Sunderland Cultural Quarter, enhancing the city’s existing flagship cultural venue at the Sunderland Empire. The new facilities will work in concert with the existing venue to ensure that consumers regard Sunderland as a genuine cultural destination. The development of the nighttime economy will both guarantee the financial viability of the associated cultural venues and allow visitors to eat, drink and engage in cultural activity all within the bounds of the Culture Quarter.

The Quarter will be both financially and environmentally sustainable, delivering new employment opportunities and economic benefits to the city, whilst using the revenue generated from the various restaurants and bars to subsidise and guarantee the delivery of high quality artistic content throughout the quarter and will form a new hub both culturally and economically, offering employment, training and volunteering opportunities to people from both Sunderland and the wider region. It will be a place where art and cultural production can take place, where people of all ages and all backgrounds will learn to dance and act and sing and write music. It will act as a magnet for artists from Sunderland and from elsewhere to come to produce and to stay. It will attract hundreds of thousands of people to come and see great art and community art, performances they know they will enjoy and new experiences that can change how they see the arts and culture. It will do all of this in an area, sitting at the heart of the city, that, in its decline, epitomised the downturn in Sunderland’s fortunes over the last decades, but which will now be regenerated and become a symbol of the city’s hope for a successful future.

Stoke on Trent

(by Paul Williams, Chairman of Stoke-on-Trent’s Cultural Destination Partnership)

Stoke-on-Trent is a polycentric, medium-sized city of six distinct towns with a population of 255,000. It boasts an unusual convergence of geography, character and cultural identity, and as a product of the industrial revolution, it is overwhelmingly the formerly dominant ceramics industry that continues to impose an evocative and distinctive landscape and indelible identity onto the region. The way the city and neighbouring borough of Newcastle-under-Lyme have developed historically is at the heart of the many issues that impact the region today. As Darren Henley, Chief Executive of Arts Council England comments “the transformative, reviving power of creativity is particularly palpable in places such as Stoke-on-Trent which have experienced the trials of post-industrialisation but have decided to rebuild the narrative of their place in a large part through investment in the arts and culture.”

The Prince’s Regeneration Trust’s successful £9 million restoration of Middleport Pottery with financial support from public funders, private donors and philanthropic benefactors provides an exemplar for the city’s approach to culture-led regeneration. Now managed by the Re-Form Heritage charity, Middleport continues to act as a catalyst for the entire regeneration of the town of Burslem and the wider city, stimulating economic growth in the area and encouraging tourism and enterprise.

Following its acquisition of the 10-acre Spode pottery factory when it closed in 2008, the council committed to preserve and regenerate the heritage site’s Grade II-listed buildings and support new-build developments to revitalise the town of Stoke. Supported by national funding bodies and public and private investment, the rebranded Spode Works continues to expand through the addition of improved visitor facilities, and is home to the Spode Museum alongside artists’ studios, developed in collaboration with the arts organisation and educational charity, ACAVA. Also included are a digital incubator, exhibition galleries and creative workspace, complemented by a boutique hotel, restaurant, tea-room and shop.

For many years, the New Vic Theatre was the only regularly funded arts organisation in the region. Working in consortium with local authorities, community organisations and other partners, they secured Arts Council funding to join the Creative People and Places programme. ‘Appetite’ has subsequently sparked a latent enthusiasm for the arts among diverse groups, and also made a significant contribution to regeneration projects delivering a richer cultural life throughout the region. Appetite’s contribution to a growth in cultural ambition was integral to Stoke-on-Trent’s bid for UK City of Culture 2021. The bid expressed the newfound confidence of the city and its future as a centre of art, craft and contemporary culture. The bidding process brought the city’s cultural organisations together to reflect on the region’s remarkable assets and to define a cultural vision for both the medium and long term. With strong leadership from the city council, both Staffordshire and Keele universities and enterprising artists, the city’s cultural infrastructure and capacity was reinvigorated.

For many years, the New Vic Theatre was the only regularly funded arts organisation in the region. Working in consortium with local authorities, community organisations and other partners, they secured Arts Council funding to join the Creative People and Places programme. ‘Appetite’ has subsequently sparked a latent enthusiasm for the arts among diverse groups, and also made a significant contribution to regeneration projects delivering a richer cultural life throughout the region. Appetite’s contribution to a growth in cultural ambition was integral to Stoke-on-Trent’s bid for UK City of Culture 2021. The bid expressed the newfound confidence of the city and its future as a centre of art, craft and contemporary culture. The bidding process brought the city’s cultural organisations together to reflect on the region’s remarkable assets and to define a cultural vision for both the medium and long term. With strong leadership from the city council, both Staffordshire and Keele universities and enterprising artists, the city’s cultural infrastructure and capacity was reinvigorated.

B Arts and the British Ceramics Biennial joined the New Vic on the Arts Council‘s national portfolio and now benefits from sustained funding and support from foundations such as Paul Hamlyn and Esmée Fairbairn to develop cultural opportunities which deliver economic, social, health and education impacts. The existence of high-net-worth individuals linked to the city provides support for many arts projects including the YMCA’s Creative Youth Minds scheme through the Bertarelli and Denise Coates Foundations. Cultural businesses such as AirSpace Gallery, Claybody Theatre and Restoke, often cited as exemplar projects of people-led change, have grown in many of the city’s disused industrial buildings with new forms of investment and by operating in an entrepreneurial way. With the city council pledging £52 million capital investment to support the city’s cultural infrastructure, hotel development and the refurbishment of the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery to create a new home for its famous Spitfire plane, additional funding was secured from locally-owned corporate partners alongside successful Cultural Destinations and Heritage Action Zone bids.

The cultural anchors referenced above, together with representatives from the Cultural Education Partnership and Cultural Forum have engaged with the Stoke Diaspora to constitute a new network of organisations with expertise in culture, industry, education and civic leadership. ‘Stoke Creates’ will act as a landing platform for resources that aim to support and up-scale the city’s cultural development.

About the authors…

Paul Callaghan CBE is a philanthropist and the chair of the Leighton Group. He also chairs the Sunderland MAC Trust, a catalyst for the development and promotion of music, arts and culture within Sunderland. The Trust seeks to leverage the digital revolution to engage local people of all ages and backgrounds into dance, poetry, literacy, singing and art.

Paul Williams is the chair of Stoke-on-Trent’s Cultural Destinations Partnership, a vehicle to connect local organisations working in art, tourism and culture. It utilises this network to promote the city’s rich year-round cultural offerings. He was formerly the Head of Programmes at Staffordshire University Business School.