We look at the Queen’s Honours List and the challenges of celebrating philanthropy.

UK Foreign Aid Cut: Philanthropists cannot be expected to pick up the slack.

The UK Government has seen off a challenge to its plans to cut foreign aid from 0.7% of Gross National Income to 0.5%, with the vote falling 333-298 in the House of Commons yesterday.

The government had announced this cut in November 2020. The explanation given was that the pandemic had precipitated a difficult economic situation, meaning the UN-backed target of 0.7% could not feasibly be attained this year.

The Gates Foundation is thought to be one of the world’s largest. Image from The Independent.

Following the original announcement, a consortium of philanthropists and charities – including Bill and Melinda Gates – pooled a one-year £100m fund to pick up part of the shortfall. The consortium will fund vital services abroad, like disease prevention and family planning.

While Bill and Melinda Gates have become household names in international giving for their transformative work on preventable diseases in Africa, they are far from alone in seeking to tackle global issues. Other glowing examples are easy to find:

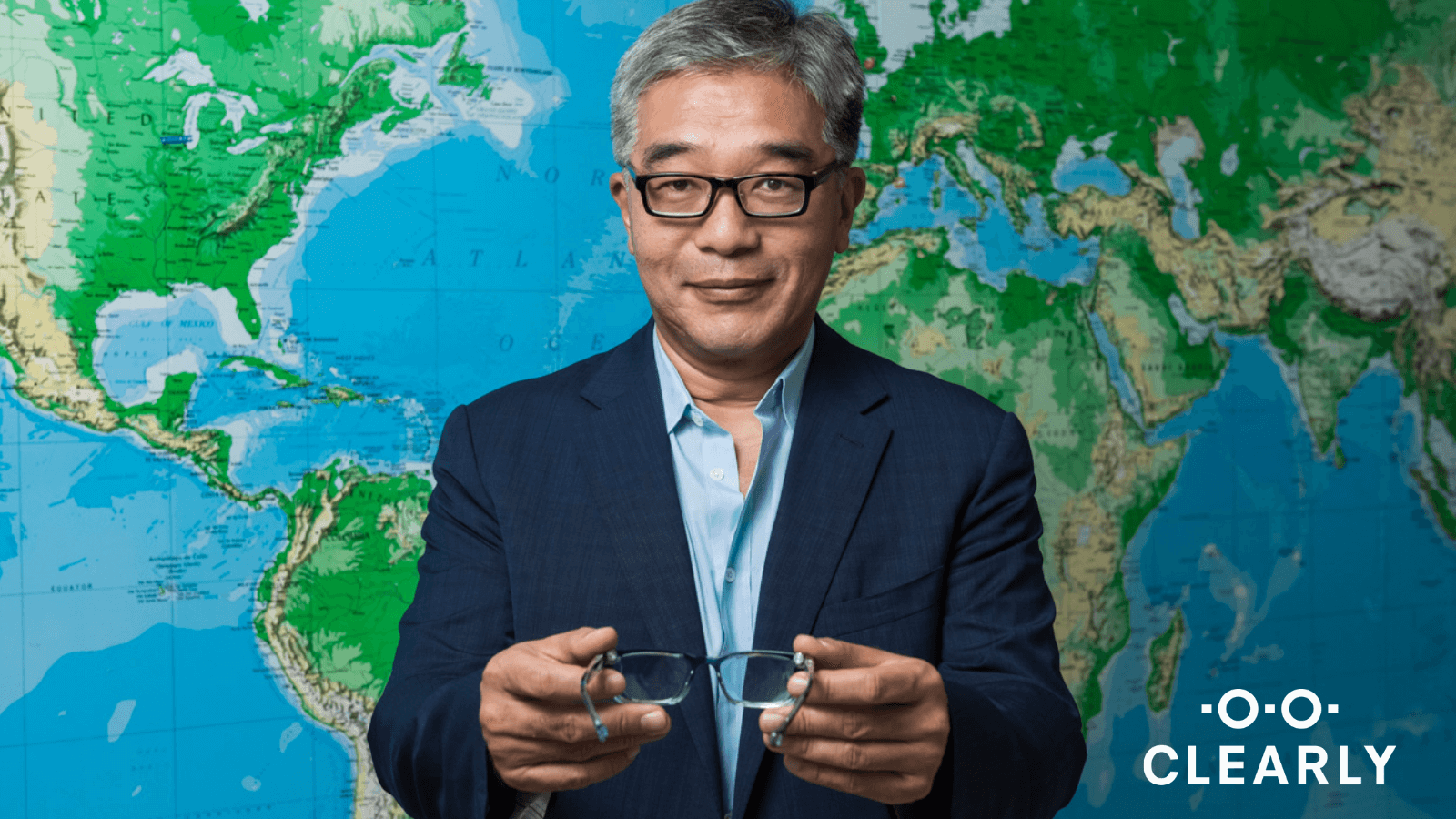

- James Chen, who played an essential role in helping Rwanda to become the first developing country in history to deliver access to primary eyecare for all its citizens;

- John Studzinski, whose work through Arise is helping to tackle modern slavery and develop transparency in business supply chains internationally, and;

- Mackenzie Scott, who is making waves in the mainstream media through the speed and size of her global donations, part of a commitment to give away the majority of her estimated $60b wealth during her lifetime.

Although the consortium’s fund will have positive impacts, it only accounts for one fortieth of the estimated £4b funding shortfall caused by the cut. This should serve as a reminder that even the best efforts of philanthropists are no match for solid government funding.

And this is understandable: the role of philanthropists is not to replace government spending, but to supplement it. Private funders are most effective when they are pursuing innovative and risky solutions to social issues. For the philanthropist, grant money is risk-capital which can uncover fantastic new ways of solving social problems. They are best placed to fund solutions where the government can’t, for fear of being seen to waste taxpayer money.

James Chen’s efforts helped bring primary eyecare to Rwanda.

Governments around the world have undoubtedly faced unprecedented challenges in balancing national needs and international responsibilities. There may be unique circumstances when philanthropy can provide temporary relief, especially for international projects that are too vital to fail, but this is not a long-term solution.

During yesterday’s session, the Prime Minister said that foreign aid “was not an argument about principle, the only question is when we return to 0.7%.”

What is needed now, then, is clarity on when this will happen. If we want international organisations to plan how they can maintain the essential services they provide around the world, this clarity is essential.

Philanthropists have a role to play in stimulating foreign development, but their role needs to be as a complement to – not a substitute for – state funding.