Enjoy this? Read article two in the series.

In a series of three articles, Scott Greenhalgh, former executive chair of Bridges Evergreen Holdings, will share his thoughts on the landscape for impact investing in the UK. This first article tackles the definitional challenge for investors and philanthropists, considers the level of returns an investor can expect and places impact investing within the wider sustainable and responsible investing landscape.

– See bottom for more on the author –

What is Impact Investing?

The definitional challenge: impact investing

“Impact Investing” is a term first used by the Rockefeller Foundation in 2007. A definition from the Global Impact Investing Network in 2009 is of:

“investments made into companies, organisations and funds with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return”.

Using the GIIN definition, impact investing can be said to be:

- Underpinned by values and the intention to have a positive effect on social and/or environmental issues;

- Requiring the impact to be measured;

- Capable of, indeed should, generating a financial as well as an impact return.

A values-based approach and intentionality are therefore central to impact investing. These values and intentionality should operate at the level of the investee company and arguably also at the level of the investor or fund manager.

At the investee company level, this means that the products or services of that business not only seek to do well they also seek to do good, or in the language of the Impact Management Project (IMP)1, these businesses seek to contribute solutions to social or environmental issues.

Values and intentionality should also underpin the desire of the investor to support the investee company in this and be reflected in the way the investor conducts its own business. The implication of this for a potential investor in an impact fund is that they should ask about the impact criteria that the fund manager uses for investment selection, how the fund manager will seek to positively influence the level of impact post investment and how impact success affects the incentives for the fund management team itself including on exit.

Implicit in intentionality is the ability to influence the actions of the investee companies and to stimulate an increase in the positive impact, over and above that which would have occurred anyway. This is often referred to as additionality.

For this reason, I define impact investing as requiring investors to take positions of influence and to actively support an increase in the positive impact, which means that I consider impact investing to be more relevant to private companies rather than publicly traded companies, where the influence of each shareholder is less. My definition is capable of embracing both material equity positions (in companies/projects) or debt positions that convey an ability to influence the impact outcomes.

Impact investing also requires the impact to be measured and measurement operates both at the level of the investee company and also at the level of the investor. The highly regarded IMP impact management framework has sought to become an industry standard and is used by many organisations, including Bridges.

Impact investing is expected to generate financial returns. This distinguishes it from philanthropy. I define impact investing as being investment in for-profit companies and use the term social investment to define lending (with a financial return) to charities and other not-for-profit entities.

The question of investor returns

But what level of financial return can be expected by an investor? And what level of risk is associated with the return opportunity? For the broader sustainability sector, a 2019 study2 by Morgan Stanley analysed 10,723 mutual funds’ performance over the period 2004-2018 and concluded that there was no trade-off in financial returns between sustainable and more traditional funds. Indeed, sustainable funds reduced downside risk and so in aggregate offered investors better risk adjusted returns.

A 2017 Wharton study3 analysed the financial performance of 53 impact funds that invested in private companies. The analysis concluded impact funds that sought to achieve market-rate returns were largely able to do so, again suggesting there is no trade-off in returns. Against this, a Stanford study4 in the same year queried whether many of the impact funds that sought market returns, could really be classed as “impact” funds as opposed to more traditional private equity and venture capital style funds that by virtue of investing in sectors such as health and education, could label themselves as impact funds. (This is a theme I return to in a later article).

It is fair to say that the relationship between risk, return and impact is quite nuanced. It is therefore important for investors to look carefully at how each fund manager addresses each of these three dimensions and the relationship between them.

A framework for responsible investing

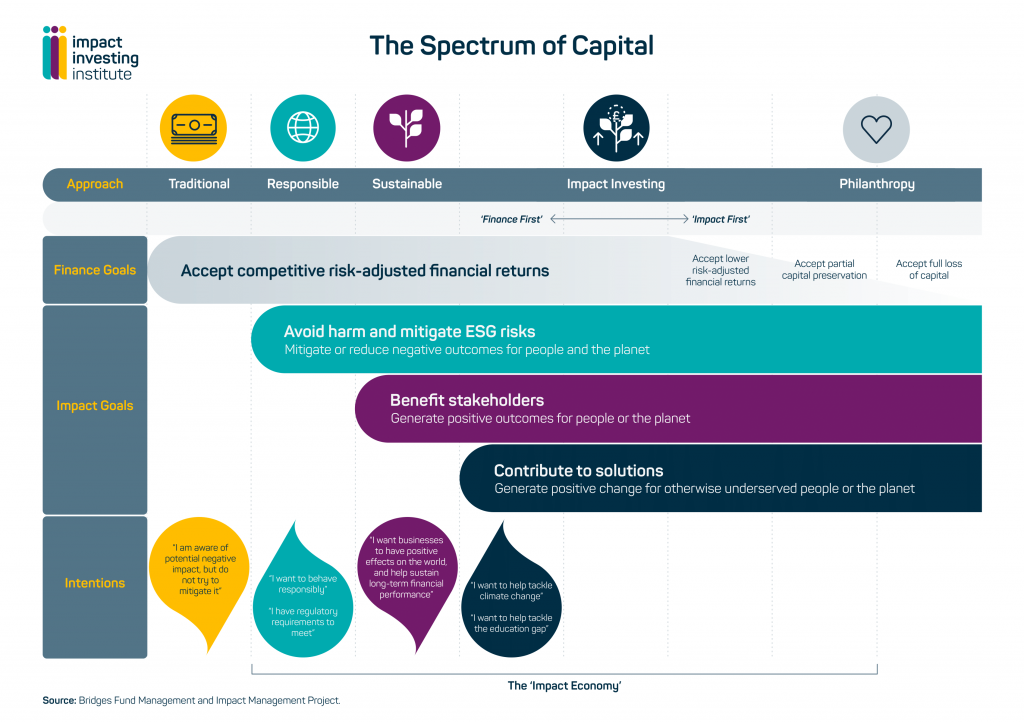

The Impact Investing Institute’s “Spectrum of Capital”5 offers a helpful way to think about all investing as being on a continuum between traditional investing that is concerned only to maximise risk adjusted returns, with no thought for the wider societal or environmental consequences of that investment decision, and philanthropy which is motivated to deliver the greatest impact return and is accepting of the full loss of capital.

As we journey from left to right, the impact goals of the investment increase. Using the Impact Management Project’s ABC framework, the first stage is to avoid harm or “A”. This involves negative screening. For example, investment strategies that exclude gambling, pornography and tobacco stocks or companies with poor labour or environmental practices would be avoid or “A” strategies. Many mainstream fund managers offer “ethical” equity and bond funds that follow the “A” methodology.

The next stage is to look for investments that are deemed to benefit stakeholders or “B”. Here companies and investors need to both avoid harm and consider positive impacts on people and/or the planet. For example, a food retailer might have a clear strategy to reduce the carbon and/or plastic footprint of its business with measurable targets. The “B” methodology is generally referred to as “sustainable” investing. As with ethical funds, mainstream fund managers offer a wide range of sustainable equity and debt funds; investments focused on addressing climate change would in most cases be classified as sustainable.

At the third stage the overall impact of the investment is taken into account and is assessed as to whether it contributes (“C”) to solutions for social or environmental issues. The desire to contribute to solutions, conveys intentionality and it is this that enables “C” investments to be considered impact investments. As noted above, I consider the need for intentionality to limit “C” investing to private market funds, both private equity and private debt.

Figure 1: Impact Investing Institute’s Spectrum of Capital

Integrating ESG

Another term frequently associated with impact investing is ESG, which stands for environmental, social and governance factors. ESG factors are implicit within the Spectrum of Capital. In order to analyse if a company avoids harm, benefits stakeholders or contributes solutions, relevant ESG factors need to be reviewed.

At its core, ESG requires companies to consider a range of non-financial matters that have a bearing on their brand, operations, employees, wider stakeholders and environmental footprint. ESG analysis and reporting can be seen as offering a framework for risk analysis for the companies and investors alike. For investors, ESG analysis gives a rounder picture of a company and its risk profile than financial metrics alone. The EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (“SFDR”) comes into force in March this year and is a first step in requiring ESG disclosure by certain investment firms.

Finally, a note of caution. The above Spectrum of Capital is but one version that shows impact investing as distinct from other impactful investment approaches. There are other versions of the spectrum of capital that refer to these other categories also as “impact investing”6 and so define the impact investment market as much larger.

Finance first and impact first

The Spectrum of Capital shows impact investing on the continuum with it sub-dividing between finance first and impact first. Finance first returns are expected to be at the prevailing market rate, in other words investors can achieve positive impact with no sacrifice to the financial returns a non-impact investor would seek with the same investment. As noted above, the Wharton article offers a positive view and the Stanford one takes a more sceptical stance as to categorising finance first as impact investing.

Impact first investing implies some level of financial return compromise. This compromise can arise because the investor knowingly accepts a lower than market financial return in the pursuit of greater impact and/or because the investor is prepared to take much greater risk of loss in pursuit of the impact goal, for example by funding innovative high potential impact start-ups.

I will return to the distinction between finance and impact first in the third article and conclude this article with an example of an investment that presents a low risk of financial loss with associated low financial return but offering high impact. This would be characterised as an impact first investment.

The Ethical Housing Company

At Bridges Evergreen we looked for impactful and investable solutions to issues of pressing social need. One such issue is the increasing level of housing vulnerability in the UK with growing numbers of vulnerable households unable to access social housing and therefore dependent on the private rental sector for their homes. This has contributed to more failed tenancies, poor quality housing and homelessness.

Evergreen founded The Ethical Housing Company (‘EHC”) in Teesside in partnership with a Social Lettings Agency. The idea was to buy property, make it decent and let it at affordable rents to those in housing need. We aimed to demonstrate that supportive and intensive housing management would enable vulnerable tenants to sustain their tenancies and this positive social impact could be linked to an asset-backed investment offering financial returns of around 3% – 4% per annum to investors. This is below the 5% targeted by other market return property funds. If successful, we believed EHC could scale up in Teesside and be a model replicated by others elsewhere in the country.

Evergreen founded The Ethical Housing Company (‘EHC”) in Teesside in partnership with a Social Lettings Agency. The idea was to buy property, make it decent and let it at affordable rents to those in housing need. We aimed to demonstrate that supportive and intensive housing management would enable vulnerable tenants to sustain their tenancies and this positive social impact could be linked to an asset-backed investment offering financial returns of around 3% – 4% per annum to investors. This is below the 5% targeted by other market return property funds. If successful, we believed EHC could scale up in Teesside and be a model replicated by others elsewhere in the country.

The results to date have been positive. Throughout Covid, tenant rental arrears have remained below 4% and tenancy stability has been high, which is testimony to excellent and supportive housing management. EHC has now raised external co-investment including from the Teesside local government pension fund, which will enable EHC to double in size over the next 12 months. Though still early days, EHC is seen as a pioneering model of using private impact capital to tackle a pressing societal issue.

In his next article, Scott will consider social impact investment in the UK in more detail, looking at the opportunities for investors to lend to charities and social enterprises and make equity investments in socially-driven businesses.

Footnotes:

1. See www.impactmanagementproject.com

2. Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Investing 2019; “Sustainable Reality Analysing Risk & Return for Sustainable Funds”

3. Wharton Social Impact Initiative 2017: “Great Expectations Mission Preservation and Financial Performance in Impact Investing”

4. Stanford Social Innovation review 2017; “Marginalized Returns”, Bolis and West

6. See for example www.sonencapital.com

About Scott Greenhalgh: After a career in private equity, Scott started working 12 years ago with a number of wonderful not-for-profit organisations that opened his eyes to the scale of social inequality and need in the UK. In 2016, he was fortunate to be able to combine these “two worlds” and lead Bridges Evergreen Holdings from inception. Evergreen is the UK’s first long-term capital investment vehicle for social impact investing. Scott is now stepping down from this role and this series of articles offer reflections on leading a pioneering impact first fund. The views in this article are the author’s own and expressed in a personal capacity.